It was a strange time to watch a movie about a Western terrorist group while the Middle East was on fire with predominately peaceful protests against oppressive governments; protests ignited by the suicide of Mohamed Bouazizi, a Tunisian fruit seller who set himself on fire after police confiscated his cart.

The next night, a few of us ended up gathering again and we watched Jacques Tati’s beautiful Play Time. A good movie to see when you are in someone else’s big city.)

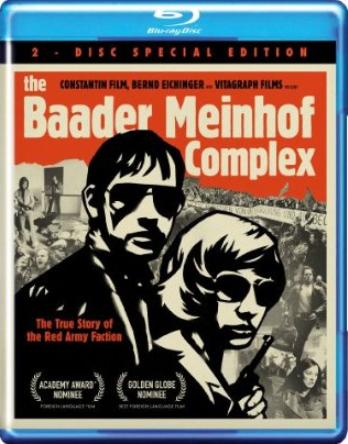

The Baader Meinhof Complex tells the story of the leftist terrorist group The Red Army Faction that was formed in Germany in 1970. The group consisted mostly of young activists but also by a well-known journalist. They were known to the public at the Baader-Meinhof Group.

The movie is so careful to include all of the details of their history that there is not so much room for the stuff in between ... like tension. Maybe a faithfulness to the details was somewhat necessary with this highly contentious history, but it probably would have functioned better in serial form on television.

The movie is good propaganda against glamour and violence. The physical exhaustion of watching so much in an endless stream really does work to create an aversion ... um, for those who don’t already have an aversion.

The particulars of the group stayed with me. Visually, the anarchy and cool of the German men and women stood out hilariously at a Jordan Fatah training camp as they proclaimed their shared fight with their Palestinian comrades.

At the camp, their volatility stood out too. They conspire against one of their own - telling the Palestinian camp leaders that this newly ostracized member is an Israeli spy. The camp leaders, seeing through the in-fighting, compassionately offer the “Israeli spy” help getting home. The Palestinian camp leaders seemed centuries older.

But the strongest particular with the Baader Meinhof Group is that they are all part of the generation of young Germans born right around or just after Hitler’s reign. They are one generation removed and the inheritors of Germany’s horrific legacy. I would guess that what some of these people had was a complex view of civilian responsibility.

A lot of us think that we wouldn’t have been complacent as Germans in Hitler’s Germany but what these people might know better than us is how abstract these problems can look like at the time and how painfully clear it all is in hindsight.

They might have been acutely aware of how ambiguous that space is in-between tolerance and complacency - especially in the present when the facts and understanding haven’t yet settled. This might be where they were coming from, in 1970, when it was becoming somewhat clear that pretty horrible things were going on in the world.

Maybe with some more distance and time, another attempt can be made to tell a story about this very old and universal problem of civilian responsibility and civilian power.

No comments:

Post a Comment